Deadlift Day: Complete Posterior Chain Workout

Deadlift day is more than just deadlifts. Here is a complete posterior chain session that builds a thick back, strong glutes, and bulletproof hamstrings.

Get a Free AI Coach on WhatsApp

Ask questions, get workout plans, and track your progress — all from WhatsApp.

Message Your CoachWhat is the posterior chain and why does it matter

The posterior chain is every muscle on the back side of your body. Specifically: the erector spinae (lower back), glutes, hamstrings, and to some extent the upper back (traps, rhomboids, rear delts) and calves. When people say "posterior chain," they usually mean the lower back through the hamstrings, but the whole system works together.

Here is why you should care: the posterior chain is the engine of your body. It is responsible for hip extension (standing up, jumping, sprinting), spinal stability (keeping your back healthy), and force production in basically every athletic movement. A strong posterior chain makes you a better athlete, a more resilient human, and frankly, it looks damn good. Nothing says "I actually train" like a thick set of erectors, well-developed glutes, and hamstrings that strain your jeans.

The problem is that most people undertraining their posterior chain dramatically. They squat (which is quad dominant), they bench (chest), they curl (biceps), and they ignore everything behind them. Then they wonder why their lower back hurts, their hamstrings are tight, and their glutes look flat.

Deadlift day fixes that. One dedicated session per week focused on the entire back side of your body.

Conventional vs. sumo: which one for you

Before we get into the workout, let me address the question I get asked most about deadlifts: should I pull conventional or sumo?

Conventional deadlift: Feet hip-width apart, hands outside the knees. More lower back, hamstring, and glute emphasis. Longer range of motion. Generally harder off the floor and easier at lockout.

Sumo deadlift: Wide stance (toes pointed out), hands inside the knees. More quad and adductor emphasis, less lower back stress. Shorter range of motion. Generally easier off the floor (for most people) and harder at lockout.

Neither is cheating. Neither is inherently better. The right choice depends on your build:

Pull conventional if: You have a short torso relative to your legs, long arms, and good hip mobility. Conventional feels natural with these proportions.

Pull sumo if: You have a longer torso, shorter arms, and wider hips. Sumo lets you get into a more upright position, which reduces the lever arm on your lower back.

Not sure? Try both for a few weeks with moderate weight. Whichever one feels more natural and lets you lift more weight with good form is your style. Some people alternate between the two across training blocks, which is also perfectly fine.

For this workout, I will write the main lift as "deadlift" and you can plug in whichever variation you prefer.

The complete deadlift day workout

| Exercise | Sets | Reps | RPE | Rest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deadlift (conventional or sumo) | 4 | 3-5 | 8-9 | 4-5 min |

| Barbell row (or chest-supported row) | 4 | 6-8 | 8-9 | 2-3 min |

| Romanian deadlift | 3 | 8-10 | 8 | 2 min |

| Hip thrust | 3 | 10-12 | 8-9 | 2 min |

| Seated leg curl | 3 | 10-12 | 9 | 90 sec |

| Back extension (weighted) | 3 | 12-15 | 8 | 90 sec |

| Face pull | 3 | 15-20 | 8 | 60 sec |

Total sets: 23

Estimated time: 65-75 minutes

This is a longer session than most of the workouts in this series, and that is intentional. The posterior chain is a big area. It includes the entire backside of your body from traps to hamstrings. Covering it properly takes more exercises than, say, an arm workout.

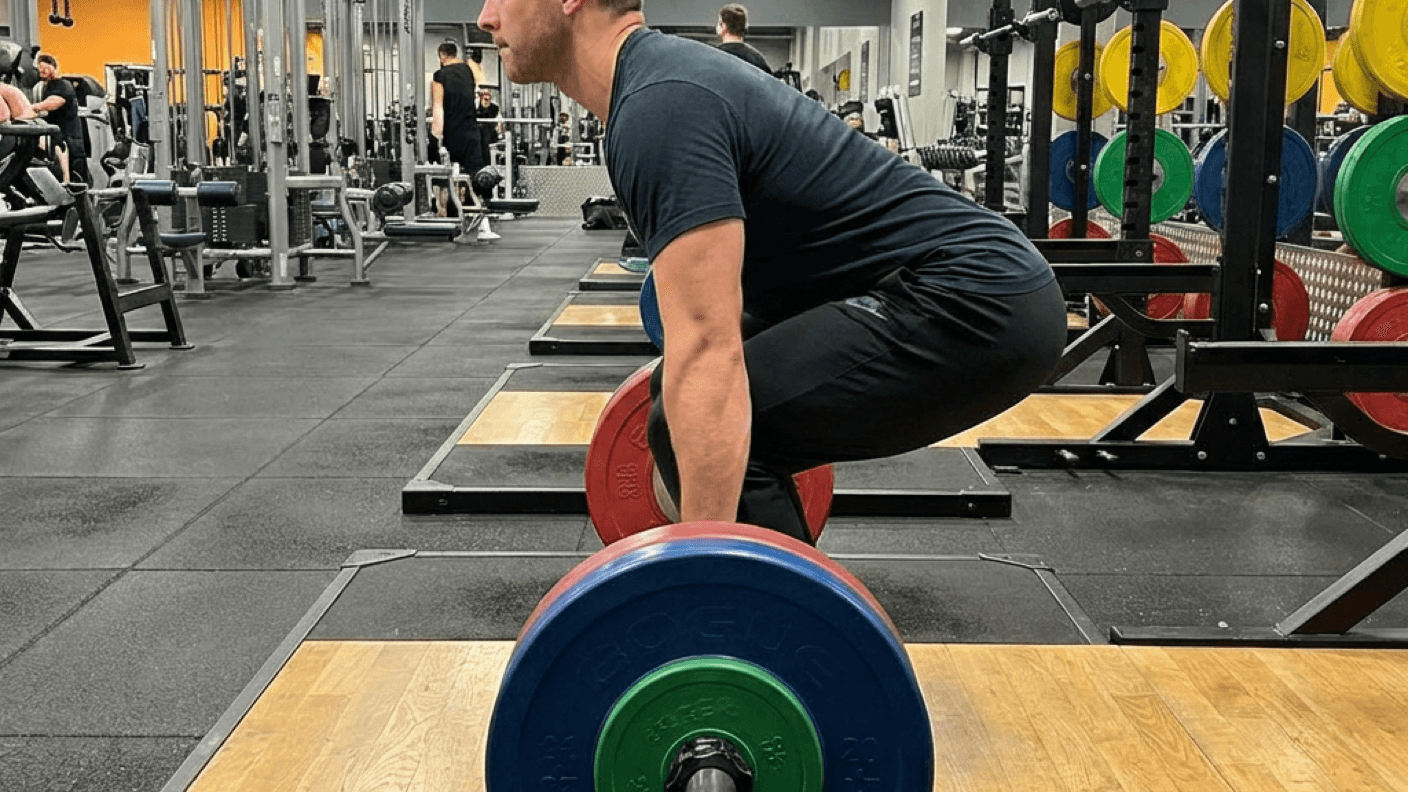

The deadlift: setup and execution

I am going to walk through the conventional deadlift step by step because I see more bad deadlifts than any other exercise. Even guys who have been lifting for years often have fundamental setup errors that limit their strength and put their back at risk.

Step 1: Walk to the bar. Stand with the bar over your mid-foot. Not your toes, not your shins. Mid-foot. Look down. You should see the bar cutting your foot roughly in half. Feet are about hip-width apart, toes pointed slightly out (15-20 degrees).

Step 2: Hinge and grip. Push your hips back and bend your knees until you can grab the bar. Hands should be just outside your knees, about shoulder-width apart. Double overhand grip to start. Do not squat down to the bar. Hinge at the hips and let your knees bend as needed.

Step 3: Set your back. This is where most people screw up. Before you pull, you need to create tension in your upper back and lock your spine in a neutral position. Think about putting your shoulder blades in your back pockets (scapular depression) and puffing your chest up. Your lower back should have a slight natural arch, not rounded and not hyperextended.

Step 4: Take the slack out. Before you lift the bar off the floor, pull gently against it until the bar makes contact with the top of the plates and your arms are tight. You should feel the weight in your hamstrings and lats. There should be no "jerk" when the bar leaves the ground. It should be a smooth transition from zero to moving.

Step 5: Drive. Push the floor away from you with your legs while simultaneously pulling back with your hips. The bar should travel in a straight vertical line, staying close to your body the entire time. It should brush your shins and thighs on the way up. If the bar is drifting forward away from your body, your setup is off.

Step 6: Lockout. Stand up tall. Squeeze your glutes, lock your knees, and stand straight. Do not hyperextend your lower back at the top (no leaning backward). Just stand up. The rep is done.

Step 7: Lower the bar. Push your hips back first, then bend your knees once the bar passes them. Reverse the path you pulled. Control the bar on the way down but you do not need to lower it at a snail's pace. A controlled drop is fine. Touch the floor, reset, go again.

Accessory exercise breakdown

Barbell row: After deadlifts, your lower back is already warm and somewhat fatigued. You have two options: barbell rows (if your lower back feels good) or chest-supported rows (if your lower back needs a break). I prefer barbell rows because they train the spinal erectors isometrically while you row, which builds back thickness and stamina. But if your lower back is screaming after heavy deadlifts, there is no shame in using the chest-supported variation.

Use a weight that is significantly lighter than your deadlift. If you pull 365, row 185-205. Overhand grip, pull to your lower chest/upper abdomen, squeeze the shoulder blades together, lower with control. No body English. If you are jerking the weight up with your hips, it is too heavy.

Romanian deadlift: This is your primary hamstring builder. Lighter weight than your deadlift, higher reps, focus on the stretch at the bottom. Push your hips back as far as they will go, feel the hamstrings load up, then drive your hips forward to stand up. Keep the bar close to your legs the entire time.

The key difference between an RDL and a deadlift is that the RDL starts from the top (standing position) and the bar never touches the floor. You reverse the movement when you feel a deep stretch in the hamstrings, usually around mid-shin or just below the knee depending on your flexibility.

Hip thrust: This is the best glute isolation exercise available. Set up with your upper back on a bench, barbell across your hips (use a pad), and drive your hips to full extension. Squeeze the glutes hard at the top for a full second. Lower slowly. I know it looks weird. Do it anyway. Contreras et al. (2015) found that the hip thrust produced significantly higher glute EMG activation than the squat, back extension, and hex bar deadlift.

Seated leg curl: Seated leg curls train the hamstrings in a flexed hip position, which biases the short head of the biceps femoris and hits the hamstrings differently than the RDL (which trains them at long muscle lengths). Doing both in the same session gives you full coverage of the hamstring musculature.

Seated is preferred over lying because the seated version keeps more tension on the hamstrings at the bottom of the movement. A 2021 study by Maeo et al. found that seated leg curls produced greater hamstring hypertrophy than lying leg curls, possibly because of the greater stretch placed on the muscle at longer lengths.

Weighted back extension: This is your lower back endurance builder. Hold a plate or dumbbell at your chest and perform back extensions on a 45-degree hyperextension bench. Controlled reps, no jerking, full range of motion. Three sets of 12-15 is enough to build the kind of spinal erector endurance that protects your lower back during heavy pulls.

Face pull: Every posterior chain day should include some upper back and external rotation work. Face pulls hit the rear delts, mid-traps, and rotator cuff muscles. Use the rope attachment, pull to your forehead, and actively pull the rope apart at the end of each rep. Light weight, high reps, focus on the squeeze.

Warm-up protocol for deadlift day

Deadlift day demands a thorough warm-up. You are about to load your spine with hundreds of pounds. Showing up cold and pulling heavy is how herniated discs happen.

Here is my warm-up sequence:

- •5 minutes light cardio (rowing machine is ideal for deadlift day because it warms up the entire posterior chain)

- •Cat-cow stretches: 10 reps. Get on all fours, arch your back up (cat), then sink your belly down (cow). This mobilizes the spine.

- •Hip circles: 10 each direction per leg. Opens up the hip joints.

- •Bodyweight Romanian deadlift: 10 reps. Practice the hinge pattern with no load.

- •Glute bridge: 15 reps. Activates the glutes before the heavy work.

Then do progressive warm-up sets on the deadlift:

| Set | Load | Reps |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bar only (135 lbs) | 8 |

| 2 | 50% of working weight | 5 |

| 3 | 70% of working weight | 3 |

| 4 | 85% of working weight | 2 |

| 5 | 95% of working weight | 1 |

| Work sets | Working weight | 3-5 |

This gradual ramp-up takes about 10-12 minutes but it ensures your muscles, tendons, and nervous system are primed for heavy pulling. Do not skip the light sets just because they feel easy. They serve a purpose.

Programming deadlifts into your training week

Where you place deadlift day in your weekly schedule matters. Here are a few rules:

Do not deadlift the day before or after heavy squats. Both movements load the lower back significantly. You need at least 48 hours between them. If you squat on Monday, deadlift on Thursday or Friday. If you squat on Tuesday, deadlift on Friday or Saturday.

Do not deadlift on the same day as heavy back work. If your pull day already includes heavy barbell rows and lat pulldowns, adding heavy deadlifts is overkill for most people. Either make deadlift day your "pull day" (like this workout does) or separate them.

Once per week is plenty for most lifters. The deadlift is the most taxing exercise you can do. It loads the entire body, from your grip to your calves. More than one heavy deadlift session per week is unnecessary for intermediate lifters and can lead to chronic fatigue. Some competitive powerlifters deadlift twice a week, but they structure it with one heavy day and one lighter technique day.

Common deadlift mistakes and fixes

Rounding the lower back. This is the most common and most dangerous error. If your lower back rounds during the pull, the load shifts from your muscles to your spinal discs. Fix: set your back before every rep (step 3 in the setup), brace your core hard, and do not attempt weights where your form breaks down. A rounded-back deadlift PR is not a real PR. It is a future injury.

Jerking the bar off the floor. If you yank the bar with straight arms, the sudden load can strain your biceps (bicep tears from deadlifts are a real thing) and throw off your positioning. Fix: take the slack out of the bar before pulling. Your arms should be taut and the bar should be in contact with the plates before your hips start driving.

Hips shooting up first. If your hips rise faster than your shoulders off the floor, you are turning the deadlift into a stiff-leg deadlift and overloading your lower back. Fix: think about pushing the floor away with your legs. Your back angle should stay constant until the bar passes your knees.

Standing too far from the bar. If the bar is over your toes instead of your mid-foot, the lever arm on your back is longer and the pull is much harder than it needs to be. Fix: walk up to the bar and stop when it is over your mid-foot. It should be about an inch from your shins.

Not finishing the rep. If you are pulling to about 95% lockout and then moving on to the next rep, you are skipping the glute contraction at the top. Fix: stand up all the way. Lock your knees, squeeze your glutes, stand tall. Then lower the bar.

When to use straps, a belt, and mixed grip

Straps: Use them on your heavier working sets if your grip is the limiting factor. Your back and legs should determine how much you deadlift, not your forearms. Train grip separately if it is a weakness (farmer's carries, dead hangs), but do not let a weak grip limit your deadlift training.

Belt: A lifting belt increases intra-abdominal pressure, which stabilizes the spine and lets you lift more weight safely. Wear one for your working sets (anything above 80% of your max). Do your warm-up sets beltless to build core strength. The belt is a tool, not a crutch. Using it does not make you weak.

Mixed grip (one hand over, one hand under): This grip prevents the bar from rolling out of your hands. It is effective but it creates an asymmetrical load on your shoulders and biceps. The underhand arm is at a slightly higher risk of bicep strain. If you use mixed grip, alternate which hand is under every set. Or better yet, use a hook grip (thumbs wrapped under the bar, fingers over the thumbs). Hook grip hurts like hell for the first few weeks but once your thumbs adapt, it is the strongest and most symmetrical grip option.

Progression and periodization

Heavy deadlifts should not increase in weight every single session once you are past the beginner stage. The movement is too taxing and the loads are too high for weekly linear progression to work indefinitely.

Here is a 6-week progression that works well for intermediates:

| Week | Working sets | Target |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4x5 at RPE 7-8 | Build volume base |

| 2 | 4x4 at RPE 8 | Slight intensity increase |

| 3 | 4x3 at RPE 8-9 | Heavier weight |

| 4 | 4x5 at RPE 7-8 (5-10 lbs heavier than week 1) | New volume base |

| 5 | 4x4 at RPE 8-9 | Push intensity |

| 6 | 4x2-3 at RPE 9 | Peak strength |

After week 6, take a deload week (2x5 at 60% effort), then start a new 6-week cycle with your new baseline. Each cycle, you should be starting 10-20 lbs heavier than the last one. Over the course of a year, that is 80-160 lbs added to your deadlift, which is legitimate progress for anyone past the beginner stage.

The accessory work does not need to follow this periodization. Keep using double progression (hit the top of the rep range, add weight) on everything else. The deadlift is the only lift on this day that needs a structured progression plan.

Build the posterior chain and everything else gets easier. Your squat goes up because your glutes and hamstrings are stronger. Your bench goes up because your upper back is thicker and more stable. Your posture improves because your erectors can actually hold you upright. And you look like someone who trains, from every angle, not just the front.