Bench Press Form Guide: Stop Making These Mistakes

Your bench press is weaker than it should be because of form issues you do not even know you have. Fix these mistakes and watch the weight go up.

The bench press is not just a chest exercise

Let me get this out of the way: the bench press is a full-body lift. I know, I know, it is "chest day" and you are benching for your pecs. But the lifters who bench the most weight (and build the most muscle doing it) understand that the bench involves the chest, shoulders, triceps, lats, upper back, and even the legs.

When someone tells me their bench is stuck at 185, the first thing I look at is their setup. Nine times out of ten, the problem is not weak pecs. It is a sloppy setup that leaks force everywhere. Fix the setup, watch the weight jump 10-20 pounds overnight.

Setting up on the bench

Your setup determines everything. A sloppy setup means a sloppy press. Here is how I teach it:

- •Lie on the bench with your eyes directly under the bar. Not under the bar, not behind it. Your eyes directly under. This gives you the right starting position for the unrack.

- •Plant your feet flat on the floor. Pull them back toward your butt as far as you can while keeping your whole foot on the ground. Your shins should be roughly perpendicular to the floor or angled back slightly. You want to feel tension in your quads, like you are pushing your feet into the floor.

- •Squeeze your shoulder blades together and DOWN. Think about putting your shoulder blades in your back pockets. This creates a stable shelf for your upper body and activates your lats. Your shoulders should not be shrugged up toward your ears.

- •Grip the bar and pull yourself up to it slightly to set your upper back even tighter. Then settle your butt back down on the bench.

At this point, you should feel tight from head to toe. Your feet are planted, your legs are tense, your upper back is a solid shelf, your shoulder blades are retracted and depressed. If you feel loose or relaxed, you have not set up correctly.

Grip width and hand position

Standard bench grip: your forearms should be roughly vertical (perpendicular to the floor) when the bar is at chest level. For most people, this means your index or middle finger sits on the ring marks of the bar, but it depends on your arm length and shoulder width.

Too narrow and you turn it into a close-grip bench, which shifts work to the triceps. Too wide and you reduce range of motion while increasing shoulder stress.

Wrist position matters a lot. The bar should sit in the heel of your palm, not high up near your fingers. When the bar is in the heel of your palm, your wrist stays straight and the load transfers directly down through your forearm bones. When the bar is up in your fingers, your wrist bends back under load, which hurts and wastes energy.

Think about punching the ceiling. That is the wrist angle you want. Straight, stacked, with the bar, wrist, and elbow in a vertical line when viewed from the side.

Some people like to use a thumbless (suicide) grip. I am not going to tell you what to do, but I will tell you that I have seen a barbell roll out of someone's hands with a thumbless grip. Wrap your thumbs. The risk is not worth whatever marginal comfort you think you are getting.

The arch: yes, you should have one

Every time someone posts a bench press video online, there are comments about "too much arch." Let me clear this up.

A moderate arch is standard bench press technique. It is not cheating. It is how the lift is performed. Here is why:

- •It shortens the range of motion slightly, which lets you move more weight. This is a feature, not a bug. A shorter ROM means more load, which means more mechanical tension on the muscles.

- •It puts your shoulders in a safer position. With your upper back arched and shoulder blades retracted, your shoulders sit in external rotation. This reduces impingement risk. A flat-back bench press with protracted shoulders is actually more dangerous for the shoulder joint.

- •It gives you a stable base. The arch creates three points of contact: upper back, butt, and feet. This tripod creates a rigid structure to press from.

You do not need a powerlifting-level extreme arch unless you are a competitive powerlifter. Just retract your shoulder blades, let your lower back maintain its natural curve, and keep your butt on the bench. That is enough arch for most people.

Unracking and the bar path

Unracking: With your eyes under the bar, press it off the hooks and bring it out until it is directly over your shoulders (roughly over your collarbone/upper chest area). Lock your elbows. This is your starting position. Do NOT start the rep from over your face or from over your belly button. Straight over the shoulders.

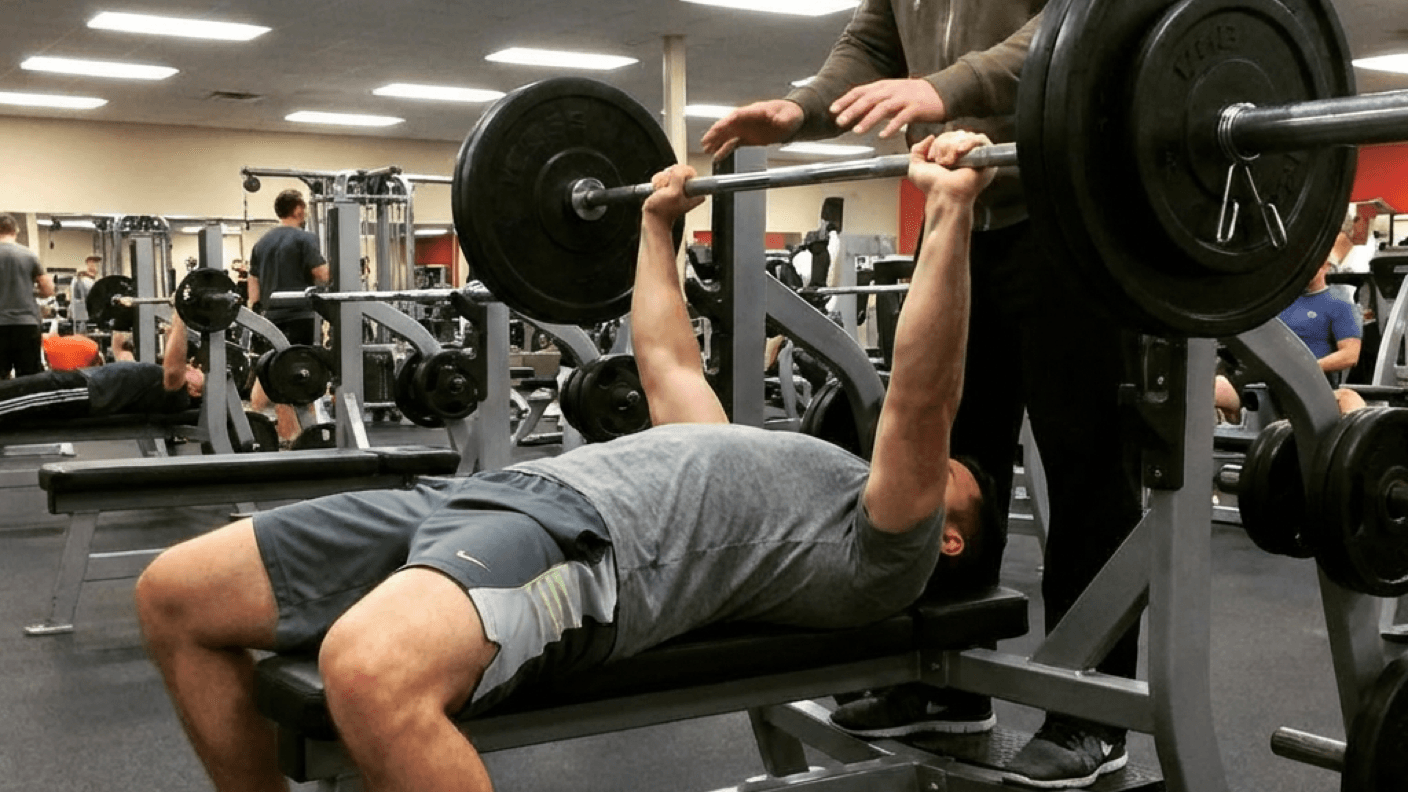

If you can, have a spotter give you a liftoff. A good liftoff preserves your upper back tightness. A bad unrack (where you have to shrug the bar off the hooks yourself) can undo all that work you did setting up your shoulder blades.

Bar path: This is one of the most misunderstood aspects of the bench press. The bar does NOT travel straight up and down. It travels in a slight diagonal.

From the top position (over your shoulders), the bar descends on a slight angle toward your lower chest/upper abdomen area. Then it presses back up in a slight arc back toward the starting position over the shoulders. From the side, the bar path looks like a shallow J-curve or reverse C.

Greg Nuckols analyzed bar paths of elite bench pressers and found this pattern consistently. The diagonal path allows your lats to contribute to the press and keeps the bar over your base of support throughout the movement.

The descent: where to touch

The bar should touch somewhere between your nipple line and the bottom of your sternum. The exact spot depends on your arm length, grip width, and arch height, but for most people it is right around the nipple line or slightly below.

Key points on the descent:

- •Tuck your elbows about 45-75 degrees from your body. Not flared out at 90 degrees (shoulder wrecker) and not pinned at your sides (that is a close-grip bench). About a 45-degree angle is where most people should start. As the weight gets heavier, you might tuck a bit more.

- •Pull the bar down with your lats. Yes, your lats. Think about rowing the bar to your chest. This keeps your upper back engaged and controls the descent.

- •Touch your chest. Every rep. Not hover-above-your-chest, not slam-it-off-your-sternum. A controlled touch where the bar gently contacts your chest, pauses for a split second, then drives back up. If you cannot touch your chest with the weight you are using, the weight is too heavy.

The descent should take about 1.5-2 seconds. Controlled but not excessively slow. You are building elastic energy in the stretched muscles at the bottom that helps with the initial drive off the chest.

The press: how to push correctly

Once the bar touches your chest, drive it up and slightly back toward the rack. Remember the J-curve. You are pressing the bar from your lower chest back to over your shoulders, not straight up from the touch point.

Cues for the press:

- •Push yourself away from the bar. Instead of thinking about pressing the bar up, think about pushing your back into the bench. Same movement, different mental image, and it keeps your upper back tight.

- •Drive through the heel of your palm. Keep that straight wrist. Imagine you are trying to push the bar through the ceiling.

- •Keep your shoulder blades pinned. The number one mistake on the press is letting your shoulders come off the bench at the top. This protraction of the shoulders costs you stability and puts your shoulder in a vulnerable position. Lock those shoulder blades back and keep them there for the entire set.

There will be a sticking point, usually about halfway up, where the bar slows down significantly. This is normal. Push through it. Do not let the bar drift out of the groove. If the bar starts drifting toward your face or toward your belly, the rep is out of the groove and will be much harder than it needs to be.

Leg drive: the secret weapon

Most people treat the bench press like an upper body exercise where their legs just hang out and do nothing. This is a massive waste.

Leg drive means actively pushing your feet into the floor during the press. This does not mean your butt lifts off the bench (that is a violation in competition and a form breakdown in general training). It means your legs are creating tension and force that transfers through your body into the bar.

Here is how to think about it: your feet push into the floor, which drives your body slightly toward your head (but your upper back is pinned in place by friction with the bench), which creates a horizontal force that your arch converts into a slight upward force. It is subtle, but it can add 10-20 pounds to your bench once you learn to use it.

Practice this: Set up on the bench with no weight. Get into position with your feet planted. Now push hard with your feet like you are trying to slide yourself headward on the bench. Feel how your whole body tenses up? That is leg drive. Now maintain that tension while pressing an empty bar. Once you get the feel for it, start adding weight.

The 7 most common bench press mistakes

1. Flaring the elbows to 90 degrees. This puts your shoulder in a terrible position and shifts the stress to the front delt and shoulder capsule. Tuck to 45-75 degrees.

2. Bouncing the bar off your chest. A little touch-and-go is fine for training, but if you are literally bouncing the bar off your sternum to get it moving, you are using your rib cage as a springboard. This is how you crack a rib or bruise your sternum. Control the touch.

3. Pressing with a flat back. No arch, no retraction, shoulders shrugged up. This is the "I just lie down and push" approach. It is weak and dangerous. Set up properly.

4. Lifting your butt off the bench. Usually happens when the weight is too heavy and you instinctively try to decline-press it. Drop the weight or learn to use leg drive without butt-lifting.

5. Not touching your chest. Half reps build half a chest. Touch your chest on every rep. If the weight is too heavy to touch, use less weight. A study by Martorelli et al. (2017) found that full ROM bench press produced significantly more muscle growth than partial ROM, even when the partial group used heavier loads.

6. Pressing the bar straight up instead of back. The bar should travel in a J-curve. Pressing straight up from the low touch point puts the bar in front of your shoulders at lockout, which is an unstable position.

7. Death grip on the bar. Squeezing the bar as hard as you physically can creates unnecessary tension in your forearms and can actually make the press harder. Grip firmly but do not white-knuckle it.

Programming for a bigger bench

The bench press responds well to both volume and frequency. Here is what I have found works best at different levels:

| Level | Frequency | Weekly volume | Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beginner | 3x/week | 12-15 sets | Linear progression, form practice |

| Intermediate | 2-3x/week | 10-15 sets | Weekly progression, rep PRs |

| Advanced | 2-4x/week | 12-20 sets | Block periodization, variations |

Beginner program (first 6-12 months):

- •Bench press: 3x5 adding 5 pounds every session

- •Once you stall, switch to 3x5 adding 5 pounds per week

- •That is it. Simple linear progression. You do not need board presses, pin presses, or accommodating resistance. You need more practice and more food.

Intermediate approach:

- •Day 1: Competition bench 4x4-6 @ RPE 8

- •Day 2: Close-grip bench or paused bench 3x6-8 @ RPE 7-8

- •Optional Day 3: Light speed bench 5x3 at 60-65% of max

- •Add weight or reps week to week

Accessory work that actually helps your bench:

- •Dumbbell bench press (addresses imbalances, increases ROM)

- •Overhead press (builds front delt strength)

- •Barbell rows (strengthens the lats for bar control)

- •Dips (chest and tricep mass)

- •Tricep pushdowns and overhead extensions (lockout strength)

If your bench is stuck, here is my diagnostic flowchart: If you fail off the chest, you need more chest and front delt work. If you fail at lockout, you need more tricep work. If you fail in the middle, you probably need to bench more frequently to improve your technique through the sticking point. And if everything just feels heavy, eat more food and sleep more. Sometimes the answer is that boring.